Events Upcoming

New Members

Service and Retail Workers Emerge as Heroes

Like many of us, Lance Anderson recently went to the supermarket, where an orange-vested employee was wiping down carts with sanitizer and telling customers about the rigorous cleaning practices being done inside the store.

"What they were trying to do was give everybody a level of comfort," says Anderson, a Dallas-area consultant who previously worked in the retail industry and who holds a SHRM-SCP.

Eric Oppenheim, who once ran a Burger King franchise in the Washington, D.C., area, picked up a meal at a chain restaurant. He, like other customers, was able to walk through a roped-off area to the counter, but the cashier wouldn't accept his physical currency by hand.

"I had to put it in a tray," says Oppenheim, who holds a SHRM-SCP and now consults with restaurant businesses. "They took the tray, then took the money and put it in the register. Is that safer than me just handing them the money? I don't know. But … I was impressed with the fact that they had a system in place focusing on minimizing physical contact with guests."

Virtually overnight, the paradigm has shifted for parts of the service and retail industries that are allowed—or able—to stay open for business amid the pandemic.

Supermarkets have installed sneeze guards at checkout lanes and affixed floor markers designed to keep shoppers at an appropriate distance as they approached the point of sale. Some stores are limiting the number of people allowed inside, for the safety of customers and employees alike. Walmart was one of the first to announce it would check employees' temperatures, after it and other retailers and grocers reported that employees had tested positive for the virus.

Restaurants that could retain baseline operations had to become creative, too, when dining in was outlawed and to-go orders became the only option. Fast-food giants such as McDonald's had drive-through infrastructure at the ready. In Chicago, Lou Malnati's has become adept at leaving boxed pizzas on porches or coordinating curbside pickups at its kitchens, and it has increased focus on its mail-order business.

Today, the companies that remain standing are left to wonder: What will be the new normal in the wake of the novel coronavirus?

Businesses will certainly need to have plans in place to ensure that they can contract and expand their workforces in the event of another pandemic, experts say. The most obvious holdover, though, will be the expectation that companies demonstrate safety and cleanliness in highly visible ways.

"The smart businesses are going to use this moment and continue to advocate for the health of their employees and customers and continue to use that as a positioning statement," says Baltimore-based HR consultant Joey Price, CEO of Jumpstart:HR. "It would be helpful to have that healthy sense of paranoia of making sure you're doing what you can do, within reason."

Essential Workers

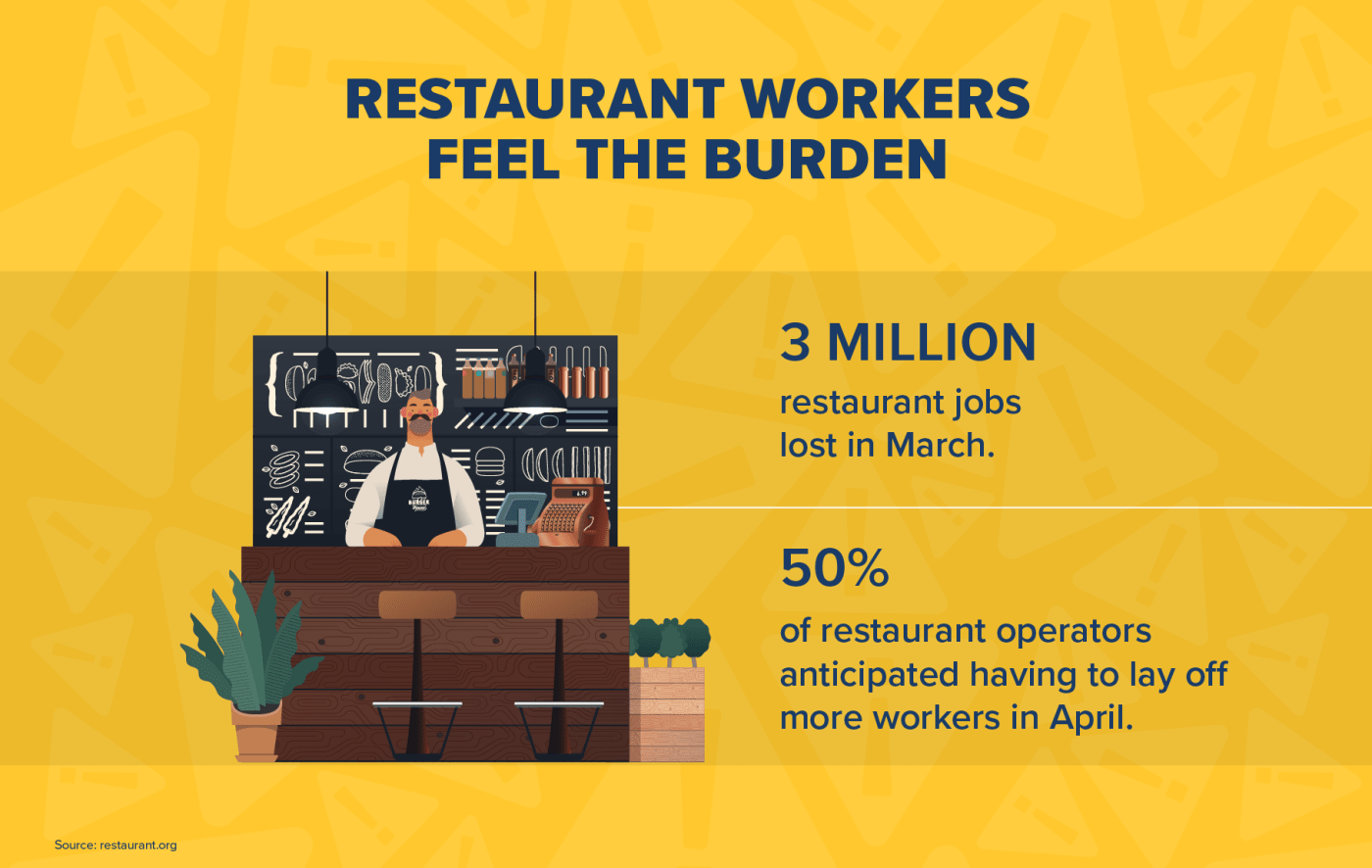

Grocery stores employ about 3 million people, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics reports, and restaurants employed more than 15 million workers before the pandemic set in, according to the National Restaurant Association. In March, the restaurant industry lost more than 3 million jobs and $25 billion in sales, and about 50 percent of restaurant operators were expecting to lay off more people in April, according to the restaurant association.

Many of these workers were part-time employees earning relatively low pay. They probably were not anyone's idea of front-line combatants. Then much of the economy was shut down in an effort to slow the spread of COVID-19, and, like first responders and medical professionals, food-supply-chain employees are expected to venture out into the world and assume a greater measure of risk while white-collar workers telecommuted from home.

They are among the majority of U.S. workers, perhaps as many as 100 million, who are in jobs that require their physical presence at a worksite, Bloomberg recently estimated.

"I think people have a new respect for grocery stores" and their employees, says Brian Brown-Cashdollar, program director for the Western New York Council on Occupational Safety and Health in Buffalo, N.Y.

Early on, the labor-rights organization urged supermarkets to adopt safety guidelines such as doing away with paper coupons, scheduling frequent hand-washing breaks for cashiers and being on guard for racism against workers of Asian descent who might face backlash over COVID-19's origins in China. The council also urged supermarket employees to take allotted breaks to avoid fatigue, to get plenty of sleep and to recognize that touching their faces even if they were wearing gloves was a bad idea.

"We talked to cashiers," Brown-Cashdollar says. "I personally observed one in a local market who was wearing gloves and spraying her hands with cleaner in between each order because she didn't know what else to do."

He says the safeguards, many of which were voluntarily adopted at supermarkets, likely will become a permanent part of the American shopping experience.

"These practices are not particularly onerous," Brown-Cashdollar says. "You can cut down on the cleaning a little bit, but social distancing makes sense to keep your workforce healthy. Some of that is probably going to stick around, especially now that we're being told we could see Round 2 [of the novel coronavirus] coming around in the fall."

The COVID-19 outbreak also has revived the issue of sick leave for part-time employees, worker advocates say. U.S. employees were told to stay home if they felt sick, but not everyone can afford to do so if they won't be paid.

"This entire crisis has really exposed so many different kinds of vulnerabilities that we have," says Yasin Khan, coordinator of public programs for the Labor Occupational Health Program at the University of California-Berkeley.

Amazon and Instacart workers in late March walked off the job to protest inadequate compensation given the risk they were taking being exposed to the virus and the lack of protective gear. Whole Foods employees held a "sickout" in early April protesting the lack of personal protective gear. At least 30 grocery store workers have died from COVID-19 so far, and about 3,000 have stopped work because they have symptoms or have been exposed, according to the United Food and Commercial Workers International Union, which represents about 1.3 million grocery store workers and food processing workers. The union is pushing for the government to classify the workers as first responders so they can access protective equipment and testing.

In some cases, grocery store chains have temporarily boosted workers' hourly pay to reflect dire new circumstances. A variety of companies have gone on hiring binges to meet greater demand for goods and services. Domino's needs an additional 10,000 full- and part-time employees to keep up with its pizza orders.

|

|

A federal regulation that allows an employee to refuse to work in unsafe conditions without reprisal may be more relevant than ever in the COVID-19 era. Typically, the U.S. Occupational Safety and Health Administration's "Right to Refuse Dangerous Work" rule has been invoked by employees in obviously high-risk fields, such as construction. A worker can engage in a good-faith protest and ask managers for reassignment if an employer doesn't immediately address his or her concerns. Employees can't be punished or denied pay for doing so, in theory. The U.S. Supreme Court sided with workers in a 1980 ruling, Whirlpool Corp. v. Marshall. The case began in 1974 when two factory maintenance workers refused to walk on suspended mesh screening at an Ohio assembly line after a series of accidents, including one in which an employee fell through the screening and was killed. The protesting workers were written up and sent home without pay, setting in motion a conflict between the manufacturer and the U.S. Department of Labor. Fast-forward to 2020. Relatively low-paid workers in the food-distribution chain have found themselves potentially in harm's way while performing jobs deemed "essential." University of Illinois labor professor Michael LeRoy says it's possible workers such as supermarket cashiers could invoke the rule if they feel their workplace has become dangerous, but it would be uncharted territory. Triggering the rule and the ensuing legal tussles can be costly and time-consuming for people who aren't represented by strong unions, LeRoy says. "The rule itself is geared toward industrial workplaces," he says. "When it was promulgated, there was no expectation of a pandemic."—M.R. |

| Expanded HR Role |

With time of the essence, employers are expediting hiring and onboarding procedures and aren't always waiting for applicants' drug tests and background checks to clear. Increasingly, companies are conducting interviews by phone or videoconference—the type of efficient, high-tech measures the retail industry had already adopted during the tight labor market of recent years.

Expect to see more end-stage hiring moved to the Internet, says Andrew Challenger at outplacement firm Challenger, Gray & Christmas in Chicago.

"We're going to have a lot of companies say this process is faster, it's cheaper and potential employees will like it more when it's done as virtually as possible," he says. "This crisis is forcing a lot of organizations to invest more deeply in the hardware, the software and the creation of policies around it."

If there's a silver lining in any of this, says Anderson, the Dallas-area consultant, it's that HR professionals stand to raise their profiles as they're tasked with planning and implementing changes, especially at small and midsize companies that don't have specialty divisions to handle them.

This is similar, he says, to the way HR professionals inherited duties to plan for active-shooter scenarios.

"HR has a unique opportunity here to be the local hero," Anderson says. "When anything new throws the status quo into turmoil, if it's not keyed specifically to operations, oftentimes HR becomes the catchall."

Leading the Way

To aid members whose employees are still cooking carryout orders, the National Restaurant Association has launched an educational campaign emphasizing more vigilant sanitization efforts and precautions when partnering with delivery drivers who work independently through app-based platforms such as Uber Eats.

"It has to be a very symbiotic relationship to make this work," says Larry Lynch, the restaurant association's senior vice president of science and industry.

Oppenheim, the restaurant consultant, says that sector is well-positioned to lead because of its strong culture of food safety.

"I would argue that the rest of the country is catching up to where we are in the restaurant business in terms of hand washing, in terms of preventing cross-contamination, in terms of following good hygiene practices," he says.

He notes that the now-popular advice about washing your hands for 20 seconds—the time it takes to sing "Happy Birthday" twice—has been around for years in the restaurant sector.

The new reality may not become apparent for some time, says Price, the Baltimore-based HR consultant, especially if COVID-19 resurfaces periodically.

But cues could come from the nimblest of entrepreneurs. He notes several food vendors in his city's Cross Street Market complex stayed in business by developing a carryout system with a centralized distribution point.

"What we'll see are perhaps some innovations from business to adapt," Price says.

However, recovery won't come overnight.

"We're not going to snap back from this situation," Challenger says. "Companies that are trying to lure people into their workplaces are going to be focused on cleanliness, on disinfecting their facilities. Those are the types of measures that HR is really going to be responsible for, in a lot of ways. Keeping the workplace safe now means biologically."

This article is provided by the Society for Human Resource Management (SHRM)